Make Decisions and Resolve Conflicts

Learning Objectives

After completing this unit, you’ll be able to:

- Explain key methods for decision-making.

- Describe key methods for conflict resolution.

Decision Making and Prioritization Methods

There are some basic methods to help a group come to a decision or prioritize. In these moments, it’s critical to help stakeholders feel like a united team rather than their constituent perspectives. You may be helping the group prioritize high-level goals or in-the-weeds features, or they may be deciding which audience segment to serve first or which creative direction to pursue. The same methods can be useful at different levels and different moments within the design process.

Dot Voting

Ask participants to choose their favorite options by placing dot stickers on the corresponding sticky notes, and discuss their rationale.

Decision Checklist

Create a checklist of considerations you want the group to use as a basis for decision-making. Include specific business, customer, and societal goals outlined in challenge framing, and process considerations like whether or not diverse voices are having a due influence on their own perspectives. Your checklist should be specific to your project.

Criteria Scorecard

Similar to the decision checklist, a criteria scorecard should list criteria you want decision-makers to evaluate. Instead of a yes/no, stakeholders grade each option (idea, concept, or priority) based on each criteria listed, on a scale of 1–5.

Criteria for the scorecard should be more specific than on a decision checklist and may use the project’s Jobs to Be Done.

Stakeholders can compare the cumulative grades they gave each option and discuss individual grades given. This method can uncover different people’s interpretations of the options and reveal collective opinions.

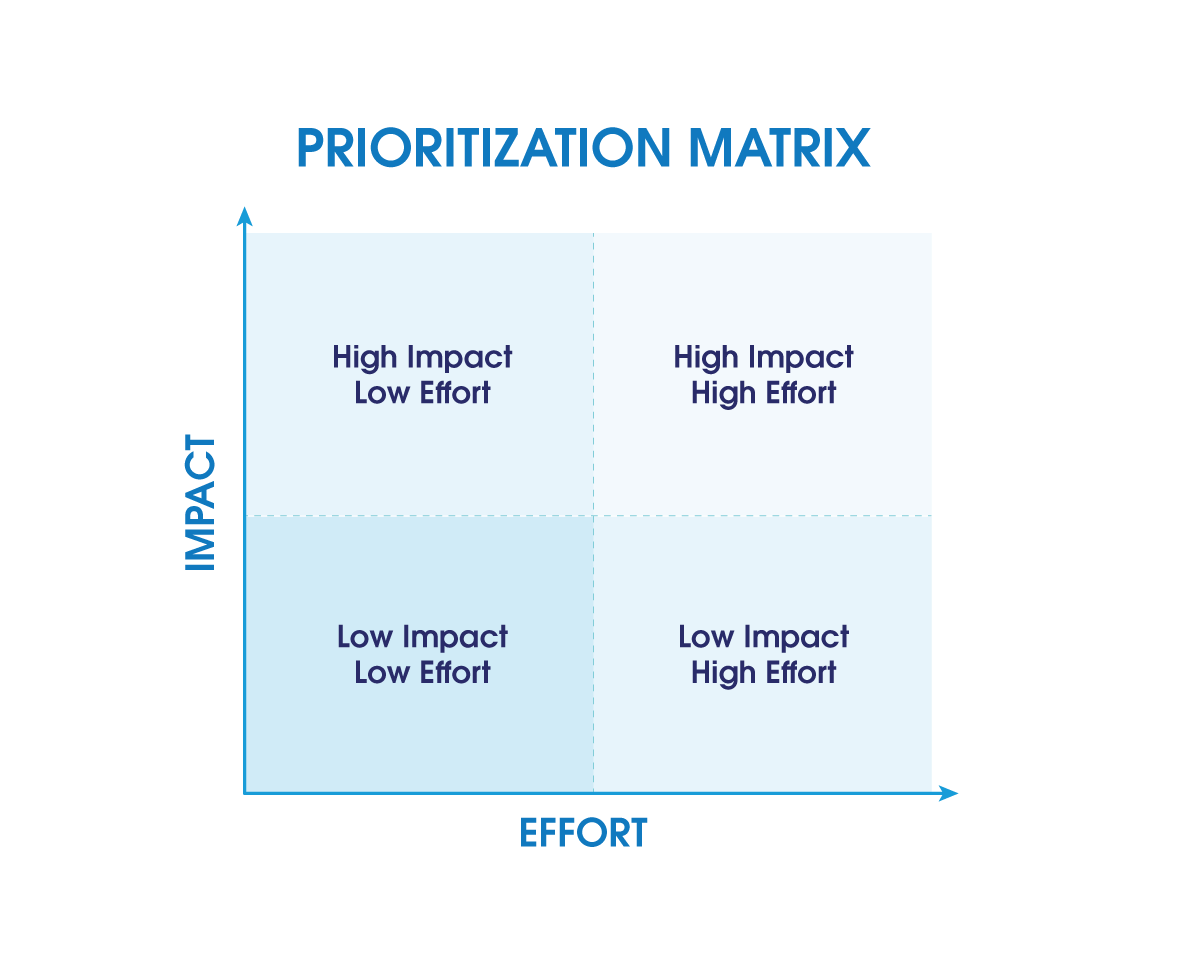

Prioritization Matrices

When you can simplify the key criteria, or you have a lot of options to consider, use prioritization matrices. First the strategy designer defines two axes based on your key criteria, and draws a diagram that shows the axes with a scale like high/low or more/less.

A classic example of a prioritization matrix is an Impact/Effort analysis. Impact (high and low) is one axis, and effort (high and low) is the other.

A classic example of a prioritization matrix is an Impact/Effort analysis. Impact (high and low) is one axis, and effort (high and low) is the other.

Then stakeholders plot all the options relative to one another on this diagram one at a time, discussing their relative merits and risks, and any differences in opinion about placement.

Groups can create multiple prioritization matrices for the same set of options, using different sets of key criteria to see how the same options fare with different criteria priorities.

Trade-Off Scales

This method helps the group sort through and align on priorities. First, create a short list of factors, options, or features, listing no more than 10. Then visualize a ranking scale with the same quantity of numbers on it. So if you have five factors, your ranking scale is 1–5; if you have 10 factors, your ranking scale is 1–10.

Ask each stakeholder to rank the options individually, keeping in mind the value to the business, customer, and society. No two options can be ranked the same; you’re forcing choices using this method.

Then have stakeholders discuss the differences in their rankings, and their rationale.

Conflict Resolution Methods

Conflict resolution should be very tailored to the needs, personalities, and context you’re working in. We can’t cover every scenario here, and you’re not always going to reach a consensus or find the compromise that makes everyone happy. But here are some best practices to help groups resolve friction and come to alignment on a plan they can support.

Get Curious

If you or your design team gets defensive about the work, channel your energy toward getting curious instead. Don’t shut down objections or challenges to the work; take them in, and see if they can make your work even better.

Get to the Heart of the Objection

Not everyone has a deep vocabulary in design or strategy. People may give feedback in the form of an alternate solution rather than explaining why your idea isn’t working for them. It can help to ask for the why behind the feedback, and then keep asking why, or “what leads you to conclude that…” or whatever you need to ask to get to the underlying reason for the concern.

Whether they dislike a color or disagree with a fundamental strategic premise, asking why repeatedly helps your teammate or stakeholder articulate something important to them, and helps you understand a perspective or constraint that wasn’t clear before. The Five Whys method was developed for initial project research but is useful in conflict resolution for the same reasons: It gets to the heart of motivations and assumptions.

Go Back to the Last Aligned Moment

Even when you’ve aligned the group several times throughout the course of a project, it can be easy to lose sight of the shared perspective. If you feel your group fragmenting into their individual mindsets and agendas rather than acting as a unified team, it may help to back up and remind everyone about the premises they already agree on.

Start with the key goals you defined before the project kicked off, and check to see if they're still the right ones. Then review the key insights from research, check in for continued alignment, and keep going one by one through all the key alignment moments in the project so far.

Either your group will be back on track, or you will discover that something has changed that impacts the group’s alignment, and therefore your project. It could be completely external and outside of your control, like when a startup disrupts the market. Or it could be that internal priorities have shifted during the course of your project.

Be open to accepting a change, even if it means backtracking in the project. Talk openly about the implications and trade-offs, as you built strategy work on that prior alignment. It can be discouraging to a team to have to redo work, but ultimately everybody would prefer that to proceeding with a vision that stakeholders don’t believe in.

Name the Challenges

When friction comes up, and you’ve been able to get to the source of it, echo back what you’ve heard to the stakeholders. This tells them you’re listening and taking concerns seriously, helps you process the objections raised, and is itself a form of alignment—albeit alignment around what’s not working. You can’t solve a problem you don’t understand, so make sure you take the time to understand challenges that come up mid-project. Then you can turn to collaborating on solutions.

Acknowledge the Value of Perspectives

When conflict about the work arises in the middle of a project, it’s because someone has been brave enough to voice a concern that’s important to them. Even if it’s inconvenient, make sure to take the time and acknowledge the value of having that person speak up. Doing so deepens the sense of psychological safety among your group and encourages others to speak their minds, too—which will ultimately improve the work.

Explore Solutions Genuinely

A conflict or objection that comes up in your stakeholder group might not resonate with you. It can be tempting to dismiss it as a lack of vision on the part of your stakeholder, or an “edge case” that isn’t relevant to the majority of your customers. Instead of dismissing the issue, it’s important to remember that there are an untold number of solutions to any given problem. Consider this an invitation to bring more creative problem-solving to bear. If someone has a seat at your proverbial table, aim to have their head nodding at the vision you’re recommending.

Invite Collaborative Problem-Solving

If your team is having a very hard time solving a given aspect of the challenge, bring more brains to the party. Having more people as thought partners and codesigners takes the pressure off of your team, enables more people to engage with your work (and become champions of it), and increases your chances of finding a solution that meets the needs of your audience. Inviting more collaborators in the middle of the project will increase the complexity of stakeholder management and potentially slow your progress a bit, so consider building codesign into your original plan, and also reserve the right to use it if your team gets stuck.

Bring in Fresh Inspiration

Changing your setting, team dynamic, or thought patterns can also help when conflict arises. There are many ways to approach creative problem-solving; sometimes bringing fresh inspiration to the challenge will unlock a new perspective and a new idea for how to solve a sticky problem.

Pause, Then Revisit

Sometimes you reach a point where you just can’t make progress in resolving a conflict. Either you keep “swirling” around the same arguments, or you can’t seem to find agreement on priorities. Sometimes there are factions of your stakeholder group trying to persuade each other of the right next step to take. If it feels like the conflict is getting less productive, take time away from the problem. Identify some further research or designing you can do to explore new options, and do what you need to do to cool emotions if needed. Then, invite the group to come back fresh and ready to begin again another day.

Be Consistent and Intentional

As you can see, you achieve alignment through a consistent and intentional effort to make sure that all the people in your system are ready and willing to help your project succeed, using various methods depending on the situation.

With all these alignment methods and best practices, you now know how to set your strategy design project up for success and create buy-in for your team’s work. You’ve never been more ready to help your organization use strategy design as a driver for business outcomes and build enduring advantage. Onward!

Resources

- Trailhead: Idea Generation

- Trailhead: Challenge Framing and Scoping

- Trailhead: Jobs to Be Done Framework for Designers

- External Site: Nielsen Norman Group: Using Trade-Off Scales for Prioritization in UX Design Projects

- Trailhead: Design as a Social Practice (See Learn About Ecosystem Mapping unit)