Take Action with Events and Functions

Learning Objectives

After completing this unit, you’ll be able to:

- Define functions

- Distinguish between function declaration and function expressions

- Invoke functions

- Pass and assign functions

- Describe uses of functions and events in Lightning Web Components

When it comes to making stuff happen in JavaScript it’s all about events and functions.

Remember our model of the runtime? Let’s extend that a bit.

With JavaScript in the browser, events are all over the place. Parts of the DOM emit events that correspond to what that DOM object does. Buttons have click events, input and select controls have change events, and virtually every part of the visible DOM has events for when the mouse cursor interacts with it (like passing over it). The window object even has event handlers for handling device events (like detecting the motion of mobile devices).

To make something happen in a web page, functions get assigned to these events as event handlers.

To reiterate, DOM events and other events related to the browser environment are not actually part of the core JavaScript language, rather they are APIs that are implemented for JavaScript in the browser.

When an event is emitted, a message is created in the engine. It is these messages that are placed in the event queue we talked about earlier.

Once the stack is free, the event handler is invoked. This creates what’s referred to as a frame on the call stack. Each time one function invokes another, a new frame is added to the stack, and when complete, it is popped off the stack, until finally the frame for the actual event handler is popped, the stack is empty, and we start all over again.

Once the stack is free, the event handler is invoked. This creates what’s referred to as a frame on the call stack. Each time one function invokes another, a new frame is added to the stack, and when complete, it is popped off the stack, until finally the frame for the actual event handler is popped, the stack is empty, and we start all over again.

Defining and Assigning Functions

In JavaScript functions are essentially special objects. As objects, they are first-class members of JavaScript. They can be assigned as the values of variables, passed into other functions as parameters, and returned from functions.

There are two essential phases in the life of a function: definition and invocation.

When function is declared, its definition is loaded into memory. A pointer is then assigned to it in the form of a variable name, parameter name, or an object property. It should be no surprise, however, that there are several different syntaxes to do this.

Function Declaration

A declaration is a statement that uses the function keyword to create a function. In fact, we’ve seen it already when we were looking at our object constructor. That constructor is a function. But constructor functions are a bit special, so let’s step back and talk about plain old functions and see how they work:

// declare function

function calculateGearRatio(driverGear, drivenGear){

return (driverGear / drivenGear);

}

// call function

let gearRatio = calculateGearRatio(42, 30);

console.log(gearRatio); // 1.4

In this code sample, function is followed by the name of the function, with parameters enclosed in the parentheses.

This works fine, but there’s some implicit stuff happening. First of all, the function name becomes the variable name. It also implicitly assigns the variable to the enclosing context. Finally, you can call this function before it is declared, such as below where calculateGearRatio is invoked the line before the declaration.

// call function

let gearRatio = calculateGearRatio(42, 30);

// function is declared after the line it is called

// this is allowed in function declaration

function calculateGearRatio(driverGear, drivenGear){

return (driverGear / drivenGear);

}

console.log(gearRatio); // 1.4

Function Expressions

Function expressions accomplish the same thing as declarations more explicitly.

const calculateGearRatio = function(driverGear, drivenGear){

return (driverGear / drivenGear);

}

// the rest works the same

let gearRatio = calculateGearRatio(42, 30);

console.log(gearRatio); // 1.4

In this instance we have an explicitly assigned variable. Since we’ve named the pointer, we can drop the function name after the function keyword. The only catch here is that the function must be declared prior to it being invoked.

Notably, function expressions are also used to assign functions as members of objects. Recall when we assigned the changeGear function to Bike.prototype?

Bike.prototype.changeGear = function(direction, changeBy) {

if (direction === 'up') {

this.currentGear += changeBy;

} else {

this.currentGear -= changeBy;

}

}

Returning a Function

Since functions are first-class objects, another way to declare a function is when a function returns another function. This pattern is often referred to as a factory function.

// when invoked, this function will assign a function

function gearFactory(){

return function(driverGear, drivenGear){

return (driverGear / drivenGear);

}

}

// calculateGearRatio can now be invoked as a function

const calculateGearRatio = gearFactory();

// and all the rest

While the above example is simplistic, it’s valid. Factory functions are useful for one-off reusable functions, especially to capture variable references in a closure. We talk about closures in a later unit.

Anonymous Functions

There are many APIs in JavaScript that require you to pass a function for them to work. Say, for instance, you have an array, and you want to create a new array derived from the values of that array. In this case you would probably use the Array.map function.

let myArray = [1, 5, 11, 17];

let newArray = myArray.map( function(item){ return item / 2 } );

console.log(newArray); // [0.5, 2.5, 5.5, 8.5]

In this snippet, myArray.map takes in a single parameter: a function that is executed once per item in myArray.

This function is never reused. It is declared as an argument (with no name...thus “anonymous”) passed into the function, and is executed in the internals of the implementation of the map function. Anonymous functions (also called lambdas in some languages) are commonplace in JavaScript.

Function Invocation

Once you’ve declared your function, you’ll probably want to get around to invoking it. When a function is invoked, a few things happen.

Remember, the first thing is a new frame is pushed onto the stack. Then an object containing its variables and arguments is created in memory. The this pointer is then bound to the object along with a few other special objects. Values passed into arguments are then assigned, and finally the runtime begins to execute the statements in the body of the function.

The binding of this has one important exception which we’ll revisit in the unit on Asynchronous JavaScript.

Invocation Versus Assignment

When working with functions, one potential source of confusion to those new to JavaScript is whether you are assigning/passing a function or invoking it. It all comes down to whether you use the ().

Consider our bike object’s calculateGearRatio function.

let bike = {

...,

calculateGearRatio: function() {

let front = this.transmission.frontGearTeeth[this.frontGearIndex],

rear = this.transmission.rearGearTeeth[this.rearGearIndex];

return (front / rear);

},

...

}

Now consider these two different ways to access the calculateGearRatio function.

// invoke function and assign value to ratioResult

let ratioResult = bike.calculateGearRatio();

// assign calculateGearRatio function to a new pointer

const ratioFunction = bike.calculateGearRatio;

In the first instance, calculateGearRatio is invoked with the result returned from the function being assigned (in this instance as a primitive value) to the ratioResult variable. On the other hand ratioFunction has simply been assigned or pointed to the calculateGearRatio function. You could then turn around and invoke it as ratioFunction().

There are reasons to assign a function to another pointer, particularly as a parameter of another function like with the Array.map() function. But any function using a this reference risks breaking, since this can point to different things at different times. More on that later.

Functions as Event Handlers

If you want a function to fire as the result of an event, it needs to be wired up to that event. Doing so makes that function an event handler. If you need access to the context of the invoking event, the function definition needs to include a single argument to serve as a reference to the event that fired it. This argument is optional.

var handleClick = function(event) {

}

Each event has properties that tell you what you need to know about that event to deal with it. For example, for click you can detect data about the click (the event type, what element fired it, coordinates of the click, and so on).

var handleClick = function(event) {

console.log(event.type); // click

console.log(event.currentTarget); // the thing you clicked

console.log(event.screenX); // screen X coordinate

console.log(event.screenY); // screen Y coordinate

}

Assigning Event Handlers via DOM APIs

In simple web pages you may occasionally see explicit assigned event handlers in the HTML.

<button onclick="handleClick(event)">

Click to Go

</button>

However modern web applications rarely use event binding in HTML. Instead, the DOM API is preferred, specifically the JavaScript Element.addEventListener() function.

First you need a reference to the HTML element. Below we’ve added an id attribute to our button and removed the onclick attribute.

Now we reach into the DOM, get the reference to the button, and assign the event listener, handleClick, by passing it in as a value (note, no parentheses).

let button = document.getElementById("clicker");

button.addEventListener("click", handleClick);

Using the DOM API gives the developer flexibility to make the UI highly interactive and responsive to what the user is doing. The developer can also remove an event listener if functionality needs to be turned off.

button.removeEventListener("click", handleClick);

You will also see anonymous functions added as event listeners.

button.addEventListener("click", function(event){

//...anonymous function body...

});

Bear in mind, anonymous functions can’t be removed using removeEventListener, as there is no pointer to pass in to identify the function.

Events and Functions in Lightning Web Components

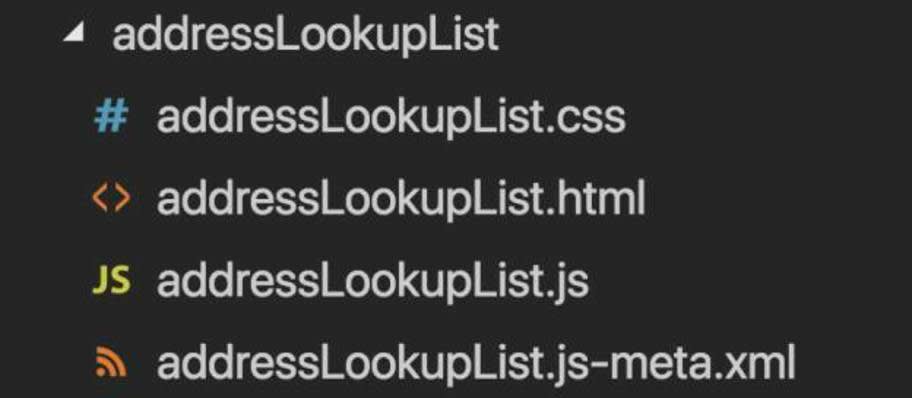

The key code artifacts of a Lightning web component are a JavaScript module, an HTML template, and a CSS file. The only one of these that is required is the JavaScript module (mind the .xml file which is also required is not code, but metadata about the component).

Functions in Lightning web components most often come in the form of methods that are members of the class exported by the component’s JavaScript module. These functions can be event handlers or other functions invoked downstream from there.

The HTML template references handler functions in a way that resembles static HTML binding, but in fact it's different. Because the template is compiled into a JavaScript artifact, the static-looking binding is in fact just a syntactic convention the framework uses for invoking addEventListener sometime in the lifecycle of your component.

This markup in the template shows event handler binding.

<lightning-input onchange={handleChange} label="Input Text" value={text}>

</lightning-input>

This is the event handler.

handleChange(event){

this.text = event.target.value;

}

Resources

-

JavaScript Functions

-

Event Handlers

- Lightning Web Components Developer Guide: Communicate with Events