Discover US Privacy Foundations

Learning Objectives

After completing this unit, you’ll be able to:

- Distinguish between privacy, data protection, and security.

- Define key privacy terms, including controller and processor.

- Describe core privacy principles, such as data minimization and purpose limitation.

- Explain how these foundations shape US privacy laws today.

Why Privacy Matters

Privacy isn’t just about compliance checklists. It’s about trust. Every time you shop online, sign up for a service, or stream a show, you expect your personal data will be treated with care. When organizations protect user privacy, they meet legal requirements and earn customer confidence.

Privacy laws set the guardrails that make this trust possible. They define what’s fair, transparent, and responsible when handling personal data. Strong privacy practices do more than check a legal box. They set a company apart from the competition. Customers are far more likely to engage with companies they trust to protect their information.

A Brief History of US Privacy

US privacy protection began long before social media and smartphones. Let’s take a minute to peel back the historical curtain:

- 1970s–1990s: Congress passed foundational laws like the Privacy Act of 1974, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA)—each designed to protect sensitive information in specific sectors.

This era also gave rise to the Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs)—a set of foundational privacy guidelines developed by the US government in the 1970s. FIPPs serve as an underlying blueprint for most modern privacy frameworks in the US and beyond and shape many of today’s privacy expectations around notice, consent, access, security, and accountability.

- 2000s–2010s: The internet quickly accelerated data collection with online services, prompting new concerns and discussions about transparency, consent, and profiling.

- Today: States lead the way with broad privacy laws modeled in part after global frameworks like the European Union’s (EU’s) GDPR. These laws all trace back to a common set of privacy concepts and principles and understanding them is the first step toward understanding how US privacy works.

Privacy, Data Protection, and Security

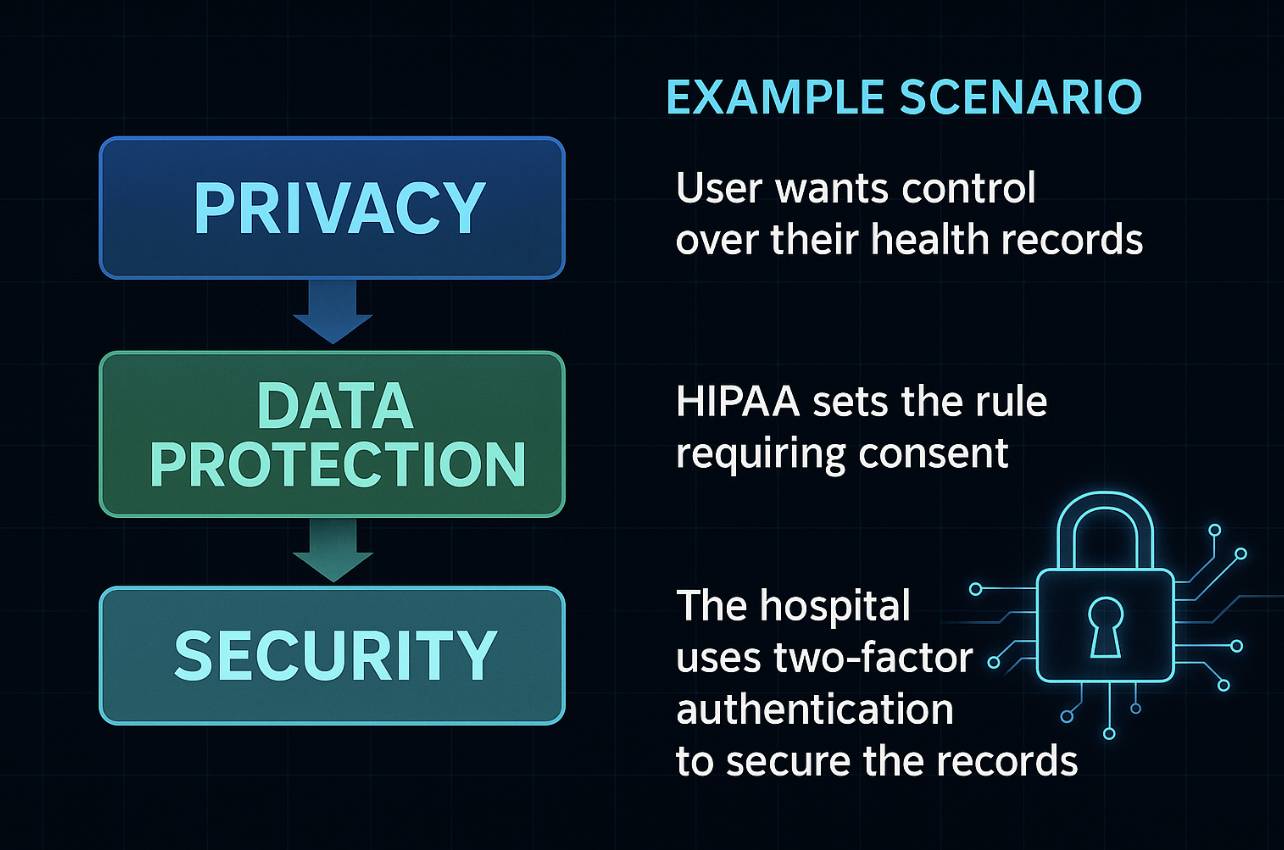

People often use these terms interchangeably. While they’re similar, they’re not identical. In the eyes of privacy laws, they serve distinct purposes. Let’s clear up some confusion and define the specific role each concept plays.

Concept |

What It Means |

Think of It As … |

|---|---|---|

Privacy |

An individual’s right to control their personal data such as what’s collected, how it’s used, and with whom it’s shared. |

The right itself |

Data Protection |

The laws, policies, and governance frameworks that uphold those privacy rights. |

The rules that protect the right |

Security |

The technical and organizational measures (like encryption or two-factor authentication) that prevent unauthorized access or misuse. |

The tools that enforce the rules |

While distinct, these concepts are deeply dependent on one another: You can’t have effective Privacy without strong Data Protection rules and the Security measures to enforce them.

Speaking Privacy: Key Terms

Before diving into specific privacy laws, let’s get fluent in essential privacy-vocabulary. Here’s a breakdown of some terms you need to know.

Term |

Meaning |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

Personal Data / Personal Information (PI) |

Any information that identifies (or could identify) an individual, such as a name, email, or phone number. |

Most US states use Personal Data (like the GDPR), while California uses Personal Information. Be careful not to confuse it with: PII (Personally Identifiable Information). PII is an older, narrower term used for specific personal data like SSNs or passport numbers. |

Sensitive Personal Data / Sensitive Personal Information |

Information that could cause extra harm or discrimination if misused such as health records, biometrics, racial or ethnic origin, or sexual orientation. |

Because this personal data is higher-risk, some state laws require stricter protections, such as obtaining "opt-in" consent before collecting it. |

Consumer |

The individual whose personal data is collected or processed. (Basically, you!) |

While most major US state privacy laws use Consumer, the EU’s GDPR uses Data Subject. |

Controller / Business |

The entity that decides how and why personal data is used. |

Most US laws use Controller like the EU’s GDPR, but California uses the term Business. |

Processor / Service Provider |

The entity that processes data on behalf of the controller, specifically under the controller’s instructions. |

Most US laws use the EU’s GDPR term Processor, but California’s equivalent is Service Provider under the CCPA. |

Why does the distinction matter? These roles aren’t just titles. Privacy laws assign different responsibilities to each. Think of a restaurant: the controller is the Head Chef who designs the menu, chooses the ingredients, and determines preparation for the staff. The processor is the Line Cook who preps the meal exactly according to the Chef's instructions. The Chef (controller) sets the strategy; the Line Cook (processor) handles the execution.

Core Privacy Principles

While specific laws vary, they’re almost all built on a set of common, fundamental principles. But where do these principles come from? Many of them are modern interpretations of FIPPs which serve as a conceptual bridge between early US privacy thinking and the modern legal obligations US organizations face today. Click through the table below to see what each principle means and how it applies in everyday scenarios.

Principle |

Description |

|---|---|

Transparency |

Be open and clear about how personal data is collected, used, and shared. |

Choice |

Give individuals control over their personal data, such as options to opt in or opt out of marketing. |

Data Minimization |

Only collect and use the personal data that’s absolutely necessary to complete the purpose or task. Less is more: If you don’t need it, don’t collect it or use it. |

Purpose Limitation |

Only use personal data for the reason it was collected—no surprise or unexpected uses. |

Individuals’ Privacy Rights |

Enable and honor individuals’ rights such as the right to know, access, correct, and delete their personal data. |

Accuracy |

Maintain accurate records and update them as needed. |

Data Retention / Storage |

Only keep personal data for as long as needed; never for “just in case.” There must be a clear reason and time frame for holding on to it. Even when there’s a valid purpose, like analyzing security logs, retention must be limited and justified. |

Security |

Safeguard personal data through technical and organizational controls like encryption, access management, and training. |

Accountability |

Demonstrate your commitment to protecting personal data through actions like data protection/privacy risk assessments, third-party audits, global compliance certifications, and ongoing governance programs. |

These principles may sound abstract at first, but nearly every major US privacy law translates these core privacy principles into legal requirements. For example:

- Transparency calls for clear notice

- Choice appears in consent and opt-out rights

- Data Minimization becomes limits on what an organization may collect

- Accountability emphasizes responsible governance and enforcement

Now that you understand the core ideas behind privacy, let’s explore how they take shape in the uniquely American “patchwork” of federal and state laws.