Get Started with Information Competency

Learning Objectives

After completing this unit, you’ll be able to:

- Describe the shift to a knowledge-based society based on the work of Peter Drucker.

- Identify the key characteristics of information competency.

- Explain why people and organizations need to develop their information competency capabilities.

Introduction

Have you ever wondered why some organizations appear to be more information-savvy than others? To help answer this question, we are going to examine the growing importance of information competency in the Knowledge Era. Before we get going, let’s establish some working definitions to frame our journey.

In this module, when referring to information, we mean data that has been processed, interpreted, organized, structured, or presented to give it meaning or purpose. Examples include reports, system specifications, marketing plans, and dashboards. In contrast, data can be thought of as raw facts and symbols that may or may not be structured or stored in a database, such as customer names, phone numbers, and the like. Knowledge can be thought of as the set of beliefs we hold to be true, that we are justified in believing, and that can guide our actions. As you can see from these definitions, knowledge is related to data and information, but they are distinctly different things.

Building on this definition, information competency is the ability to effectively:

- Determine the nature and extent of information needed.

- Access needed information effectively and efficiently.

- Evaluate information and its sources critically and incorporate selected information into one’s knowledge base.

- Use information effectively to accomplish a specific purpose.

- Understand the economic, legal, and social issues surrounding the use of information, and access and use information ethically and legally.

We probably all know some people that have amazingly good information competency skills. We probably also know at least one person that’s struggling, someone that thinks they’re great at it, and another that doesn’t even think about it. Given the rapidly growing volume of information available within organizations and online, and the massive amount of clutter and biased information, it can be a struggle to create, find, and interpret information in a way that improves decision-making and organizational knowledge. The good news is that we can improve the information competency skills in our organizations by adopting some best practices.

In this module, we start by examining why information competency is growing in importance, then we dive deep into two key areas of information competency that many organizations struggle with: (1) evaluating information, and (2) using information to formulate arguments and recommendations. Let’s jump in!

Jump Around to the Knowledge-Based Perspective

The period in which we live is like no other in human history. It’s an era in which knowledge- based capabilities are paramount. As Drucker described it, society has evolved to the point where knowledge is now the critical factor of production—above economists’ traditional factors of production, such as land, capital, labor, and enterprise. The implications are clear: to remain competitive, it is now more essential than ever for individuals and organizations to continuously develop their knowledge, and use this knowledge to better perform their jobs, such as creating innovative products and services.

|

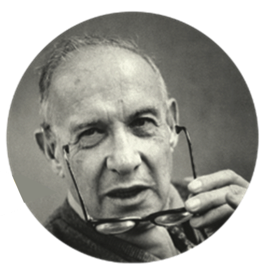

“In this society, knowledge is the primary resource for individuals and for the economy overall.” Peter F. Drucker |

While some may think such knowledge-based capabilities are mostly the responsibility of executives involved in strategic-level decision making, research has shown that innovation and performance is also linked to the knowledge-based capabilities of individuals and groups within the workforce, and knowledge at the group and organizational levels to be reliant on high-quality interactions between people. In other words, much knowledge is held in the minds of individuals, and transferred between people in the form of information. Many organizations have embraced these findings, and are actively seeking to build organizational knowledge by designing workspaces and systems to foster interactions between people that involve the exchange of high-quality information.

For example, Gard, one of the world’s leading marine insurers, is one of many organizations that have taken action to build knowledge across their organization by improving communication and collaboration. To accomplish this, Gard adopted Chatter as their enterprise social network so that their employees can work together across geographical and industrial teams, learning about each other’s markets and building trust within the company. This knowledge sharing has resulted in better risk assessments and, perhaps most importantly, collaborations to provide better risk solutions for members and clients.

As more organizations embrace knowledge sharing and collaboration tools as elements critical to their performance, the information competency skills of the people doing the sharing and collaborating will become even more essential. Good information competency skills can help us develop and share knowledge—leading to better outcomes. However, although our ability to produce and manage information is more sophisticated than ever, it probably comes as no surprise that many people and organizations continue to struggle with developing meaningful knowledge from information.

For example, a regional manager at a very large company spent countless hours looking over an incredible amount of performance information contained in dashboards, spreadsheet reports, and various systems. By working more and more hours, and drinking more and more caffeinated beverages, he kept the performance of his region consistently at or above plan. Other managers did the same. However, the overall performance of the organization was slowly declining. This went on for over two years. What the company failed to realize was that their performance metrics were overly focused on operational efficiencies instead of customer outcomes. So, while they made the data on their performance dashboards look reasonably good, customers (the one thing that mattered most) were slowly defecting to other more innovative firms. While it may seem obvious that they needed to focus more on customers, the managers were convinced that if they continued to focus on operational efficiencies, then they would be better able to help customers. To this day, their cycle of decline continues.

Looking at the example above, there was plenty of information available at the company. The managers had the customer attrition information, but they were overly focused on their operational performance key performance indicators (KPIs).

Summary

In this unit, we examined how the transition to a knowledge-based society will require people and organizations to develop their information competency capabilities. We explored an example of how enterprise social network tools, such as Chatter, can improve information exchanges needed to transfer and build group- and organizational-level knowledge. And, we walked through an example of an information competency challenge in an organizational setting. In the next unit, we’ll start looking at some select best practices to build our information competency skills.

Resources

- Drucker, P. F. (1992). The New Society of Organizations. Harvard Business Review, 70(5), 95–104.

- Drucker School—Balanced Scorecard