Imagine Future Scenarios

Learning Objectives

After completing this unit, you’ll be able to:

- Turn a signal into a scenario.

- Give your scenario a compelling storyline.

Futures Thinking Built Minority Report

Put yourself back in 1999, in the office of film director Steven Spielberg. He’s just decided to make a blockbuster movie out of the classic Philip K. Dick sci-fi short story “Minority Report,” and he has a big problem. The story is very brief, doesn’t tell you how far in the future it takes place, and says very little about the world. He’s not happy with the dystopian tone of movies like Blade Runner and 2001, and while the story itself takes some dark turns, he wants the futuristic setting to feel both realistic and hopeful.

He needs help. So he picks up the phone and convenes a sort of think-tank to bring together his filmmaking team with leading thinkers in a variety of areas of science and technology. To organize it, he taps the futurist Peter Schwartz, now the Salesforce chief futures officer. “Steven and I talked specifically about creating a new set of vernacular images of the future,” said Schwartz.

How did they do it? They spent a weekend talking about what the future could look like, ranging across every element across advertising, transportation, newspapers, food, and beyond. Virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier brought an early prototype of a VR glove. This inspired one of the most memorable technologies of the film: a pair of glovelets that Tom Cruise used to control digital displays just by gesturing in the air.

There were as many disagreements as there were ideas. And afterward Schwartz wrote up all the details in a “future history” of the world for the filmmakers. “Our goal was to get on screen a really amazing vision of the future that people would talk about,” said Schwartz. The result: “We achieved that overwhelmingly. The honest truth is that when I talk to people about the film, the thing that they remember is not the plot, it's the world.”

Sure, you’re not making a Hollywood blockbuster. You just want to be able to make some good decisions. Guess what? Creating a “movie” of a specific future possibility gives you exactly what you need to take that abstract idea and treat it like it can really happen.

Turn Your Signals into Scenarios

Say your question about the future has to do with digital interfaces, and you’ve got yourself a signal. You’ve noticed that gesture recognition has recently become a real feature of VR systems, a bit like what those VR glovelets did in Minority Report. You’ve done your digging, and you realize that this is one piece of the huge driving force known as the metaverse. The metaverse seems to be attracting an incredible amount of technology investment, so the signal feels significant.

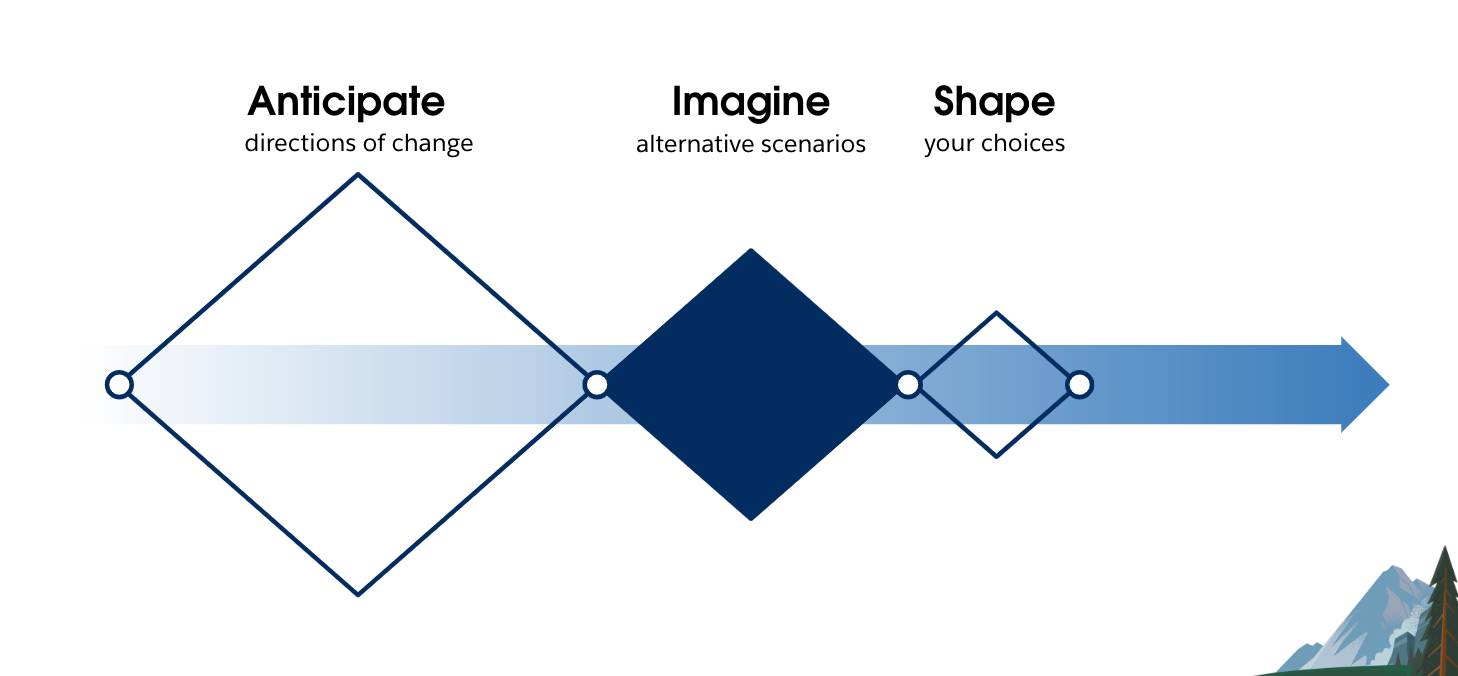

What do you do next? You imagine what it would be like if that one little signal suddenly became the new normal. What would a world look like where gesture recognition had grown up, matured, and was suddenly everywhere? In the Salesforce Futures approach, we’re now moving to the second step: Imagine alternative scenarios.

Wait, what are scenarios? Future scenarios are simply stories about the way the world might turn out tomorrow. Everyone already carries around at least one of those. That’s the ideas about what will happen that feel sensible and natural—what futurists call the baseline scenario.

Future scenarios mark off-ramps from that baseline, and there are always more than one. Scenarios are stories that can help us recognize and adapt to changing aspects of our present environment. The trick is finding the most significant possibilities to consider.

The possibilities worth exploring as a scenario have three things in common.

- Plausible: They don’t defy the laws of physics and you really do believe they can happen, even if they’re unlikely.

- Relevant: They matter to the decision you need to make.

- Challenging: They’re meaningfully different from what you would typically expect, ideally something that you would find surprising today.

Start by describing the baseline scenario, so you have that as a point of comparison. Then brainstorm five or six alternatives at a high level. And finally narrow it down to two or three that you’ll describe in more detail.

Make it a social process, shopping your ideas around to as many people as you can find who might see the world differently from you. The more diversity of thinking, the better. That’s important, because of the three characteristics, challenging is the hardest to achieve. The few failures of futures work that we have witnessed all resulted from having too few people in the conversation who could truly challenge what the others believed.

Deliver Your Scenarios Experientially

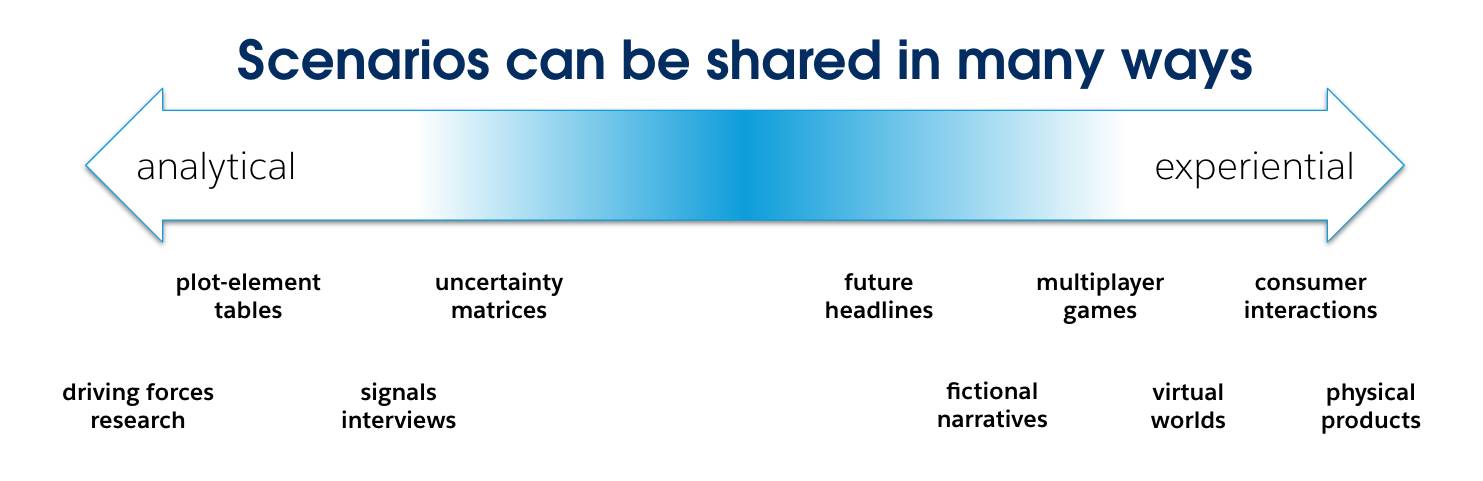

Scenarios need to be rigorously reasoned, but their power is the ability to move someone emotionally to a new realization. You have to be able to vividly imagine what situation your future self could be in and what you’ll do differently in that world to make a better decision today.

That means you need to go beyond showing you’ve done your homework with analytical descriptions of your scenarios. You have to also turn them into something experiential that will use that analysis to spark new conversations, turn up new insights, and hopefully help you make better decisions.

| Analytical Methods | Experiential Methods |

|---|---|

|

|

The art of delivering a scenario experientially is in bringing a possibility to life in a way that helps you imagine how you and others would actually act. That can’t be done in bullet points, if-then statements, or diagrams. Those are good for summarizing the logic, but you also need the only tool that allows one human to temporarily occupy the mind of another: storytelling. And yes, you really do need to occupy another mind, because neuroscience tells us that our brains regard your future self as an entirely different person. (Weird, right?)

The simplest way to do this is an exercise in what researchers call episodic future thinking, or taking a mental trip to the future, which scientists have studied for more than 20 years.

In her book Imaginable, futurist and game designer Jane McGonigal distills the method as follows. First, choose a particular moment in the future. If we’re imagining the future of alternative protein, maybe it’s the day you get a promotional text advertising that lab-grown salmon costs less than wild-caught. Then ask yourself these four questions, set a timer for 5 minutes, and free-write the answers.

| Build the scene | Make the rules | Detect opportunity | Pre-feel the future |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Where exactly am I, in my future—who else is here, and what’s around me? |

What’s true in this version of reality that isn’t true today? |

What do I really want in this future moment, and how will I get it? |

How do I feel, now that I’m here? |

Picture doing this exercise about alternative protein: Can you place yourself in a future world where many more are on the market? Let’s imagine the dreams of today’s alt-protein entrepreneurs come true. Lab-grown salmon and beef taste just the same as the real thing. They’re a bit cheaper, and they’re made locally rather than being shipped across continents and oceans.

Would your future self jump on board and give up farm-raised meat? Would you eat some farm-raised animal protein and some lab-grown? Or would you avoid it, perhaps out of concern about what this new-fangled food would do to your body?

That exercise gives you a quick back-of-the-napkin picture of the world. If you want to build it out further, you can say more about the world by choosing one of three common scenario storylines as a starting-point.

| Winners and losers | Challenge and response | Evolution |

|---|---|---|

|

The world is finite, and so one group triumphs at the cost of another. |

Problems emerge, but the various actors learn to adapt. |

Change is slow in one direction, either growth or decline. |

Other less-common scenario storylines include:

- Revolution: A sudden, dramatic, unpredictable change happens.

- Cycles: A gradual decay is followed by rejuvenation.

- Infinite possibility: A group veers into excess, thinking the world will constantly improve.

- The lone ranger: An outsider battles the system.

- My generation: A new culture arises among the youth and becomes dominant.

(For more on these storylines, see the chapter, “Composing a Plot” in the book, The Art of the Long View by Peter Schwartz.)

Let’s take your signal about gestural control. What could it look like for its path to ubiquity being a challenge-and-response? Maybe it gets popular on one platform using handheld controllers, while voice recognition and natural language processing become dominant elsewhere, forcing the builders of gestural interfaces to make the big leap of going controller-free before it breaks through to widespread use.

Now you’re off to the races! Not only can you spot signals and tie them to driving forces, you can also play with multiple storylines for how those signals could turn out to change the world.