Identify and Remove Barriers to Accessibility

Learning Objectives

After completing this unit, you’ll be able to:

- Define ableism and give examples.

- Name four types of accommodations that would improve access for people with disabilities.

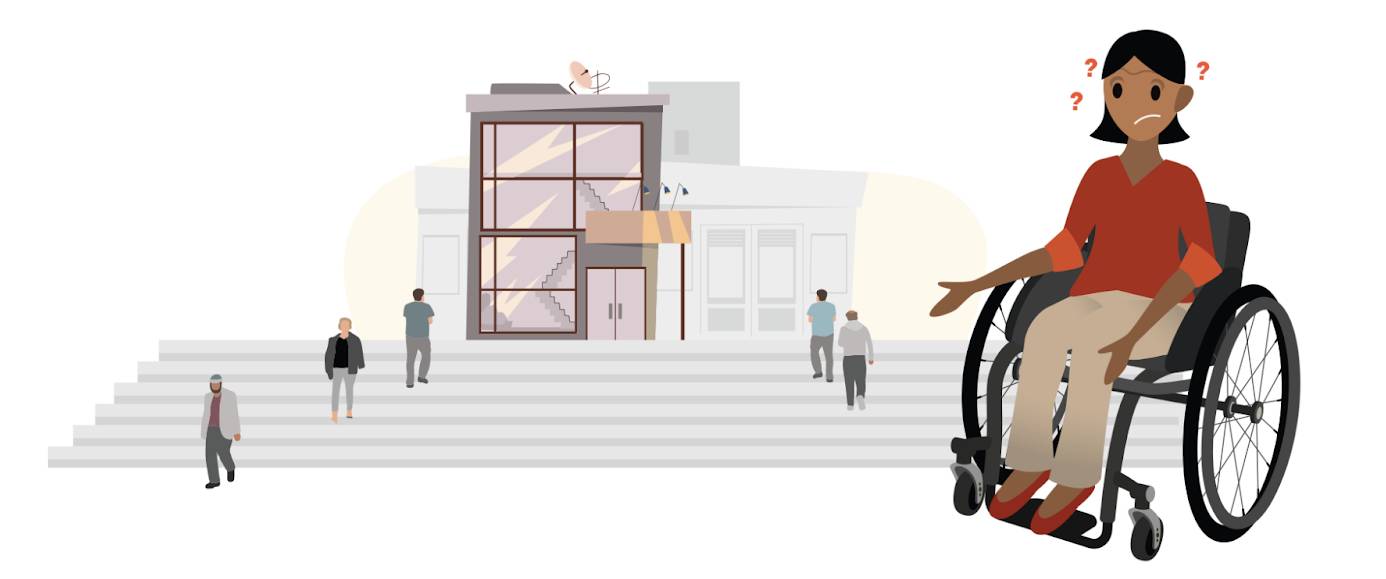

Imagine you’ve just arrived for your first in-person interview with your dream company. You made it past the screening and an initial virtual interview. Now it’s time to physically visit the office, meet your (potential) future colleagues, and generally get a sense for the feel of the company. You’re a little nervous, but mostly excited, for this next step.

You arrive at the front door of the building, already picturing yourself working here… and you realize there is no ramp to get your wheelchair up to the front door. You start to panic. Are you going to be late to the interview? How will you get inside? Who can you call?

Unfortunately, this scenario is based on a true story. And these types of occurrences happen all too often for people with disabilities.

According to the Center for Disability Rights, ableism is defined as “a set of beliefs or practices that devalue and discriminate against people with physical, intellectual, or psychiatric disabilities.”

Ableism isn’t necessarily ill-intended, but it needs to be addressed to ensure that those with disabilities have the same opportunities as everyone else. Consider these other real examples of ableism in the workplace and the communities they could have alienated.

Situation |

Impacted Community |

|---|---|

The company sends out video messages to employees without taking time to ensure the videos are captioned. |

People who rely on captioning, for example, deaf/hard of hearing community, and any person who has a disability related to verbal processing, such as neurodivergence. |

Someone asks a group of people to “stand up” or “remain standing” in an ice breaker game, without providing an alternative option for individuals who cannot or have difficulty standing. |

People who use wheelchairs or have mobility challenges. |

Weekly podcast updates are published company wide without ensuring the podcasts have quality transcripts. |

Deaf and hard of hearing community. |

These are just a few examples of practices that may disproportionately impact the disabled community. But by being aware that such practices can be exclusive, we can all take steps to address them. Here are a few best practices for creating a more welcoming and accessible work environment for all.

Best Practices for an Increasing Accessibility

1. Include alt text for images in all forms of media.

People who use screen readers, such as those who are blind or low vision, rely on alt text to understand what images communicate. Alt text also boosts search engine optimization (SEO) for companies. Alt text must be descriptive, but it doesn’t have to be long. It should be succinct, relative, and objective to the content.

As an example, maybe you send a graphic inviting employees to the next company town hall Nov. 1 at 9 AM, but you only embed the graphic in your email. Without alt text, blind- and low-vision candidates miss out on that critical information.

2. Create captions or transcripts for videos.

Automatic captioning and transcription services have increased accessibility in many ways, but they shouldn't be the fallback plan for companies to rely on. It’s still every company’s responsibility to include captions and transcriptions, and ensure they’re accurate and of high quality. This ensures that everyone can access important video content—both deaf and hard of hearing employees and also anyone in a crowded or noisy space. (This is a great example of how designing for accessibility benefits everyone.)

For example, maybe you’re sending employees a video from your company’s CEO. This can be a fast and effective method for sending out critical messages from top leadership across the company. But if the video lacks captions, or even if it has low-quality, inaccurate auto captioning, this alienates a large portion of your workforce and could send a negative message. It can also make the speaker come across as inconsiderate if what they’re saying isn’t captioned correctly.

3. Convey meaning with more than color.

Visual design can be powerful, but it’s a very limited aspect of good design. You might be accustomed to using color to quickly differentiate important content, such as application deadlines or interview dates. But color isn’t enough to make sure you’re adequately conveying your message. By accompanying text indicators, you give blind and color-blind users the same opportunity to consume your message as everyone else. Again, this approach has benefits for everyone. Full-sighted users who have screen glare, low-contrast settings, or even different mental reference points for colors will also be more likely to understand your message.

As an example, perhaps you’re hosting a job fair, with different categories of roles signified by various colors. You’ve kept those colors consistent throughout the related printed materials, digital pieces, and even in-person booth decor. Instead, consider also leveraging print titling and even imagery to accompany each color. Instead of orange representing developer roles, you might add “Developer” on all related materials and representative iconography.

4. Don’t assume everyone uses a mouse or trackpad.

Mouses and track pads get associated with computer use—but the reality is that there are many other input device options. Be sure to review text boxes, buttons, and multiple-choice fields in particular for compatibility with other input devices.

As an example, you might leverage a sophisticated virtual form for your job applications. It syncs perfectly with your candidate management system and allows for easy export. But if it’s not accessible by all, it’s not a good system! Test to make sure that the software allows submissions to be made only by keyboards—and only by screen readers. Some people will just be using one or the other.

Again, this benefits everyone. What if someone is filling out your application, and their mouse battery dies? That person would still need a way to tab through the application using their keyboard.

5. Keep language plain and concise.

Make sure your communications are clear and easy to understand. Use plain language, avoid jargon, and avoid unnecessary information and broad statements. During in-person interactions, be detailed and transparent in your feedback to help avoid any confusion.

These are good business practices in general, and they will also ensure that those who may have difficulty sifting through the “noise” in communications, such as those with ADHD, are able to absorb key points.

6. Commit to implementing a “culture-add” mentality.

“Culture fit” mentalities are problematic and often exclude folks for reasons other than their actual ability to do the job you’re hiring for. By taking a “culture-add” approach instead, you’ll start to notice how much potential and positive energy different candidates can bring to your workplace. You should always hire the most qualified candidates and make sure you are not hiring someone because of their disability or identity. Not only is it illegal, but it also is harmful to the individual and the broader community because it diminishes the skills and qualifications professionals have to offer.

Resources

- External Site: U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission

- External Site: Center for Disability Rights

- External Site: Plain Language